Some Pollutants can Travel Around the World and Increase Lung Cancer Risks

| Arthur Dominic Villasanta | | Jan 28, 2017 11:04 PM EST |

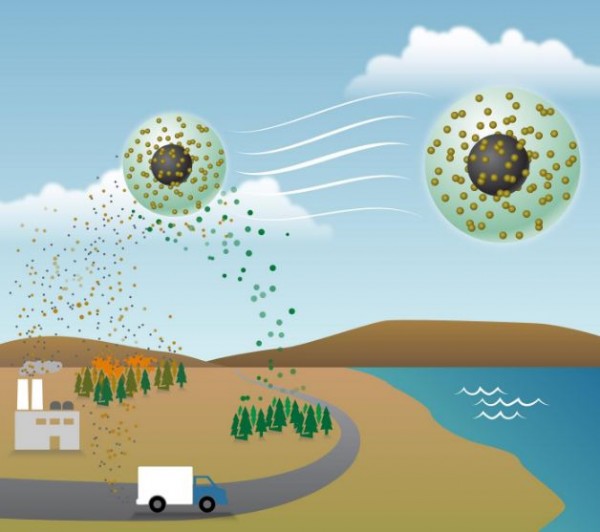

(Photo : Oregon State University) New research has revealed the ways aerosol droplets can form to transport pollutants long distances, even across oceans.

Air-polluting chemicals known as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), some of which are carcinogenic, are spread worldwide by aerosol droplets that can disperse these pollutants over long distances, even across oceans.

New research has revealed the ways that aerosol droplets can form to transport pollutants these vast distances. This new method of looking at how pollutants ride through the atmosphere has quadrupled the estimate of global lung cancer risk from PAHs, to a level that is now double the allowable limit recommended by the World Health Organization.

Like Us on Facebook

A study published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Early Edition online showed that tiny floating particles can grow semi-solid around pollutants, allowing pollutants to last longer and travel much farther than what previous global climate models predicted.

Scientists said the new estimates more closely match actual measurements of the pollutants from more than 300 urban and rural settings.

The study was conducted by scientists at Oregon State University, the Department of Energy's Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and Peking University.

Pollutants from fossil fuel burning, forest fires and biofuel consumption include PAHs. In the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency has identified several PAHs as cancer-causing agents.

PAHs have been difficult to represent in past climate models, however. Simulations of their degradation process fail to match the amount of PAH actually measured in the environment.

To look more closely at how far PAHs can travel while riding shielded on a viscous aerosol, researchers compared the new model's numbers to PAH concentrations actually measured by Oregon State University scientists at the top of Mount Bachelor in the central Oregon Cascade Range.

"Our team found that the predictions with the new shielded models of PAHs came in at concentrations similar to what we measured on the mountain," said Staci Simonich, a toxicologist and chemist in the College of Agricultural Sciences and College of Science at OSU, and international expert on the transport of PAHs.

"The level of PAHs we measured on Mount Bachelor was four times higher than previous models had predicted, and there's evidence the aerosols came all the way from the other side of the Pacific Ocean."

These tiny airborne particles form clouds, cause precipitation and reduce air quality, yet they are the most poorly understood aspect of the climate system.

A smidge of soot at their core, aerosols are tiny balls of gases, pollutants, and other molecules that coalesce around the core.

Many of the molecules that coat the core are what's known as "organics." They arise from living matter such as vegetation -- leaves and branches, for example, or even the molecule responsible for the pine smell that wafts from forests.

Other molecules such as pollutant PAHs also stick to the aerosol. Researchers long thought that PAHs could move freely within the organic coating of an aerosol.

This ease of movement allowed the PAH to travel to the surface where ozone -- a common chemical in the atmosphere -- can break it down.

"We developed and implemented new modeling approaches based on laboratory measurements to include shielding of toxics by organic aerosols, in a global climate model that resulted in large improvements of model predictions," said PNNL climate scientist and lead author Manish Shrivastava.

"This work brings together theory, lab experiments and field observations to show how viscous organic aerosols can largely elevate global human exposure to toxic particles, by shielding them from chemical degradation in the atmosphere."

Tagspolycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, PAHs, air-polluting chemicals, air pollution, Oregon State University, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Peking University, viscous aerosol, aerosols

©2015 Chinatopix All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission

EDITOR'S PICKS

-

Did the Trump administration just announce plans for a trade war with ‘hostile’ China and Russia?

-

US Senate passes Taiwan travel bill slammed by China

-

As Yan Sihong’s family grieves, here are other Chinese students who went missing abroad. Some have never been found

-

Beijing blasts Western critics who ‘smear China’ with the term sharp power

-

China Envoy Seeks to Defuse Tensions With U.S. as a Trade War Brews

-

Singapore's Deputy PM Provides Bitcoin Vote of Confidence Amid China's Blanket Bans

-

China warns investors over risks in overseas virtual currency trading

-

Chinese government most trustworthy: survey

-

Kashima Antlers On Course For Back-To-Back Titles

MOST POPULAR

LATEST NEWS

Zhou Yongkang: China's Former Security Chief Sentenced to Life in Prison

China's former Chief of the Ministry of Public Security, Zhou Yongkang, has been given a life sentence after he was found guilty of abusing his office, bribery and deliberately ... Full Article

TRENDING STORY

China Pork Prices Expected to Stabilize As The Supplies Recover

Elephone P9000 Smartphone is now on Sale on Amazon India

There's a Big Chance Cliffhangers Won't Still Be Resolved When Grey's Anatomy Season 13 Returns

Supreme Court Ruled on Samsung vs Apple Dispute for Patent Infringement

Microsoft Surface Pro 5 Rumors and Release Date: What is the Latest?