Global Warming: If An Island Vanishes, Who Owns The Sea Around It?

| David Perry | | Oct 21, 2014 11:58 AM EDT |

(Photo : Reuters) A Kiribati man looks out over the Pacific. The island nation is among the first to be swamped by sea level rise.

The islands of the South Pacific were the last land masses on Earth to be inhabited, but with sea levels rising thanks to global warming, they could be the first to be depopulated completely.

That prospect has many governments and economies contending with the thorny issue of what constitutes maritime territory when it is no longer attached to something above water, and the people have moved away.

Like Us on Facebook

For several island nations, their seas are more economically important than anything on land, and may actually be the majority of their territory. The islands of Kiribati amount to a land mass equal to that of Kansas City, but if its ocean territory is added, the nation is bigger than India.

It is a similar story across Oceania. All nations with coasts have sizable ocean holdings, up to 200 nautical miles out from land. For island countries like Kiribati, Fiji, or Palau, those waters, far from moribund, are "exclusive economic zones" and home to valuable fishing, oil, and pearling industries, amounting to several billion dollars per year.

As sea levels rise and islands become unfit for habitation, what remains (if anything), under current international regulations, becomes a "rock," with no claim to the waters around it.

In the South Pacific, the loss of an island means the loss of a population or sovereign nation, with rights and international recognition. Current international law has no provision for when a whole population is forced into exile when their home effectively drowns; Kiribati is less than two meters above sea level and is expected to be one of the first nations to be submerged.

This has many international law experts calling for expanding what constitutes an "island" to include land reclamation efforts. Others suggest nations buy territory from a willing seller, and set up shop elsewhere. Kiribati has done just that, purchasing territory in Fiji. Tuvalu approached Australia and New Zealand.

And it is not just islands in the Pacific; Bahrain, Malta, and the nations of the Caribbean all face the prospect of mass migration, and in doing so, leaving valuable submarine resources behind.

Some experts suggest that if an island nation is swamped, its borders remain intact and held in trust as an asset for the country's population, wherever they go.

The Boston Globe cites Rosemary Rayfuse of the University of New South Wales in Australia on the issue:

"An equitable and fair solution," she says, "would be the recognition in international law of a new category of State, 'the deterritorialized state.'"

This speculative status would allow island nations, even if they lost their land, to keep both their nationhood and their maritime zones, despite not having a terrestrial possession.

Landless nations already exist; the Knights of Malta, a 900-year-old religious order, has a seat at the United Nations and issues its own passports and license plates. Its members are subject to international law, and its own self-imposed statues. Their example, Rayfuse suggests, provides a seamless way to incorporate submerged nations into the international community.

Tagsglobal warming, sea level rise, Kiribati, Fiji, Australia, new zealand, Migration, Palau, Malta, Knights of Malta, Oceania, South Pacific

©2015 Chinatopix All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission

Cimate Change hasn't Greatly Affected Forests in the Eastern U.S.--Yet

Cimate Change hasn't Greatly Affected Forests in the Eastern U.S.--Yet Newly-discovered Ocean Microbes Eat Most of the World’s Methane

Newly-discovered Ocean Microbes Eat Most of the World’s Methane Study: Climate Change and Temperature Rise Drives Fishes to Cooler Water Poles

Study: Climate Change and Temperature Rise Drives Fishes to Cooler Water Poles Plants Reduce Carbon Dioxide Buildup by 17%

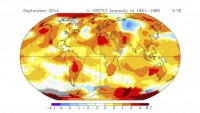

Plants Reduce Carbon Dioxide Buildup by 17% 2014 on Track to be the Warmest Year since 1880

2014 on Track to be the Warmest Year since 1880 NASA Data Reveals Earth's Deep Oceans aren't Heated by Climate Change

NASA Data Reveals Earth's Deep Oceans aren't Heated by Climate Change

EDITOR'S PICKS

-

Did the Trump administration just announce plans for a trade war with ‘hostile’ China and Russia?

-

US Senate passes Taiwan travel bill slammed by China

-

As Yan Sihong’s family grieves, here are other Chinese students who went missing abroad. Some have never been found

-

Beijing blasts Western critics who ‘smear China’ with the term sharp power

-

China Envoy Seeks to Defuse Tensions With U.S. as a Trade War Brews

-

Singapore's Deputy PM Provides Bitcoin Vote of Confidence Amid China's Blanket Bans

-

China warns investors over risks in overseas virtual currency trading

-

Chinese government most trustworthy: survey

-

Kashima Antlers On Course For Back-To-Back Titles

MOST POPULAR

LATEST NEWS

Zhou Yongkang: China's Former Security Chief Sentenced to Life in Prison

China's former Chief of the Ministry of Public Security, Zhou Yongkang, has been given a life sentence after he was found guilty of abusing his office, bribery and deliberately ... Full Article

TRENDING STORY

China Pork Prices Expected to Stabilize As The Supplies Recover

Elephone P9000 Smartphone is now on Sale on Amazon India

There's a Big Chance Cliffhangers Won't Still Be Resolved When Grey's Anatomy Season 13 Returns

Supreme Court Ruled on Samsung vs Apple Dispute for Patent Infringement

Microsoft Surface Pro 5 Rumors and Release Date: What is the Latest?